18 May 2023: Human Study

Anxiety and Depression Survey and Analysis of Hospital Staff in a Designated Hospital in Shannan City During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Peijin Zhang1ABCDEFG*, Liling Tang1BCDE, Deji Ciren2BCDEDOI: 10.12659/MSMBR.939514

Med Sci Monit Basic Res 2023; 29:e939514

Abstract

BACKGROUND: The aim of this study was to evaluate the psychological status of anxiety and depression of hospital staff in the designated hospital in the city of Shannan during the COVID-19 pandemic in order to provide a theoretical basis for effective psychological intervention.

MATERIAL AND METHODS: A cross-sectional survey was performed from September 10 to 16, 2022, by administering an online questionnaire to the hospital staff on duty in the hospital. We collected participants’ demographic and general information. The Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) and Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS) were used to investigate the anxiety and depression of hospital staff.

RESULTS: Among 267 hospital staff, anxiety was found in 98 individuals, with a prevalence of 36.70%. Depression was found in 170 individuals, with a prevalence of 63.67%. Anxiety combined with depression was found in 84 individuals, with a prevalence of 31.46%. The prevalence of depression was higher in women, Tibetan personnel, hospital staff with primary or lower titles, staff without career establishment, and non-aid Tibetan personnel, and the differences were all statistically significant (P<0.05). The SDS scores of depression in Tibetan hospital staff, nurses, hospital staff with primary or lower titles, and staff without career establishment were higher, and the differences were all statistically significant (P<0.05).

CONCLUSIONS: The prevalence of depression among hospital staff in the designated hospital in the city of Shannan was relatively high during the COVID-19 pandemic. Continuous attention and positive mental health intervention are of great importance for specific at-risk populations.

Keywords: Anxiety, Depression, Hospital Staff, COVID-19, Humans, Female, COVID-19, Cross-Sectional Studies, Pandemics, SARS-CoV-2, Personnel, Hospital, Surveys and Questionnaires, Hospitals

Background

COVID-19 was the largest public health emergency since the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome in 2003. On January 30, 2020, the World Health Organization announced that COVID-19 was listed as a public health emergency of international concern, after causing 100 000 people worldwide to be infected in just 4 months [1]. As the core force of the rescue team, hospital staff were faced with the challenges of high work intensity, heavy tasks, irregular work and rest, confinement measures, widespread media coverage, and high risk of infection [2,3]. Long-term exposure to these extreme-pressure environments had different degrees of impact on their mental health, such as anxiety and depression, which greatly affected their physical and mental health, quality of life, and work efficiency [4–6]. An umbrella review indicated that sleep disorders and depressive and anxiety symptoms had the highest prevalence among hospital staff during the COVID-19 pandemic. A meta-analysis of 30 studies showed that the prevalence of anxiety and depression among frontline healthcare workers was 43% and 45%, respectively [7]. Anxiety is often manifested in symptoms such as insomnia, excessive worry, fear, and irritability, while depression is manifested in depressed mood, loss of interest and pleasure, and fatigue [8]. Co-occurring depression and anxiety are related to more serious and protracted clinical processes, greater disability, and higher suicide risk than is either category of disorder alone [9].

After the asymptomatic infected patients appeared in the city of Shannan on August 8, 2022, Shannan People’s Hospital, as the only designated hospital in the city, was responsible for the treatment of confirmed patients, nucleic acid sampling, and supporting shelters. Most of the hospital staff were in contact with COVID-19 for the first time, with insufficient practical experience and increased psychological pressure. The purpose of this study was to investigate and analyze the mental status of hospital staff in Shannan People’s Hospital during the COVID-19 pandemic. On this basis, we further analyzed the differences of mental health among hospital staff with different characteristics, hoping to provide a reference basis for implementing targeted countermeasures.

Material and Methods

An online cross-sectional survey was conducted from September 10 to 16, 2022. The investigation period corresponded to the rapid increase of the COVID-19 pandemic in Shannan. We announced our study’s survey to the entire population of 300 hospital staff at Shannan People’s Hospital who were on duty during this period. Owing to unwillingness to participate in the survey, 33 participants were excluded from the data set. A total of 267 questionnaires were recovered, and after logical examination, 267 valid questionnaires were included, with an effective rate of 89%. That high inclusion rate may be related to the hospital philosophy of cohesion and mutual support. We included only those participants who were on duty during the survey, knew the content of the survey, and voluntarily participated. We excluded participants who were not willing to participate in the survey or could not complete the questionnaire for some other reason.

In this study, the questionnaire was conducted based on a “Wenjuan Xing” survey platform through WeChat. At the beginning of the questionnaire, participants were informed that the survey was performed anonymously, and no privacy data were involved. To ensure the response rate, participants were informed that all questions should be answered. The questionnaire was composed of 3 parts: basic characteristics, Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS), and Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS).

Anxiety was evaluated using the SAS, developed by Zung in 1971 [10]. The scale comprises 20 items. A 4-point scale is used, with 1 indicating no or very little time and 4 indicating most or all of the time. The scores of the 20 items are added up and multiplied by 1.25, with the result being the standard score, with a full score of 100 points. Based on the total score, participants are categorized as having mild anxiety, 50–59; moderate anxiety, 60–69; and severe anxiety, ≥70 [11]. The SDS, also developed by Zung, is a self-rating scale used to assess the subjective feelings of participants’ depression status and comprises 20 questions [12]. The scores of the 20 items are summed and multiplied by 1.25, with a full score of 100 points. Participants are rated as having depression with a score ≥53, and scores 53–62, 63–72, and ≥70 indicated mild, moderate, and severe depression, respectively [13]. We also compared participants’ SAS and SDS scores with the SAS and SDS scores of the domestic norm.

For this study, electronic consent was obtained from the participants, and approval was obtained from the local ethics committee. This study followed the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki.

The data were analyzed using SPSS version 26.0 for Windows (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). Categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. The chi-square test was used to compare differences in the categorical variables between groups. Normally distributed continuous variables were expressed by mean±standard deviation (SD). The single-sample

Results

PARTICIPANT CHARACTERISTICS:

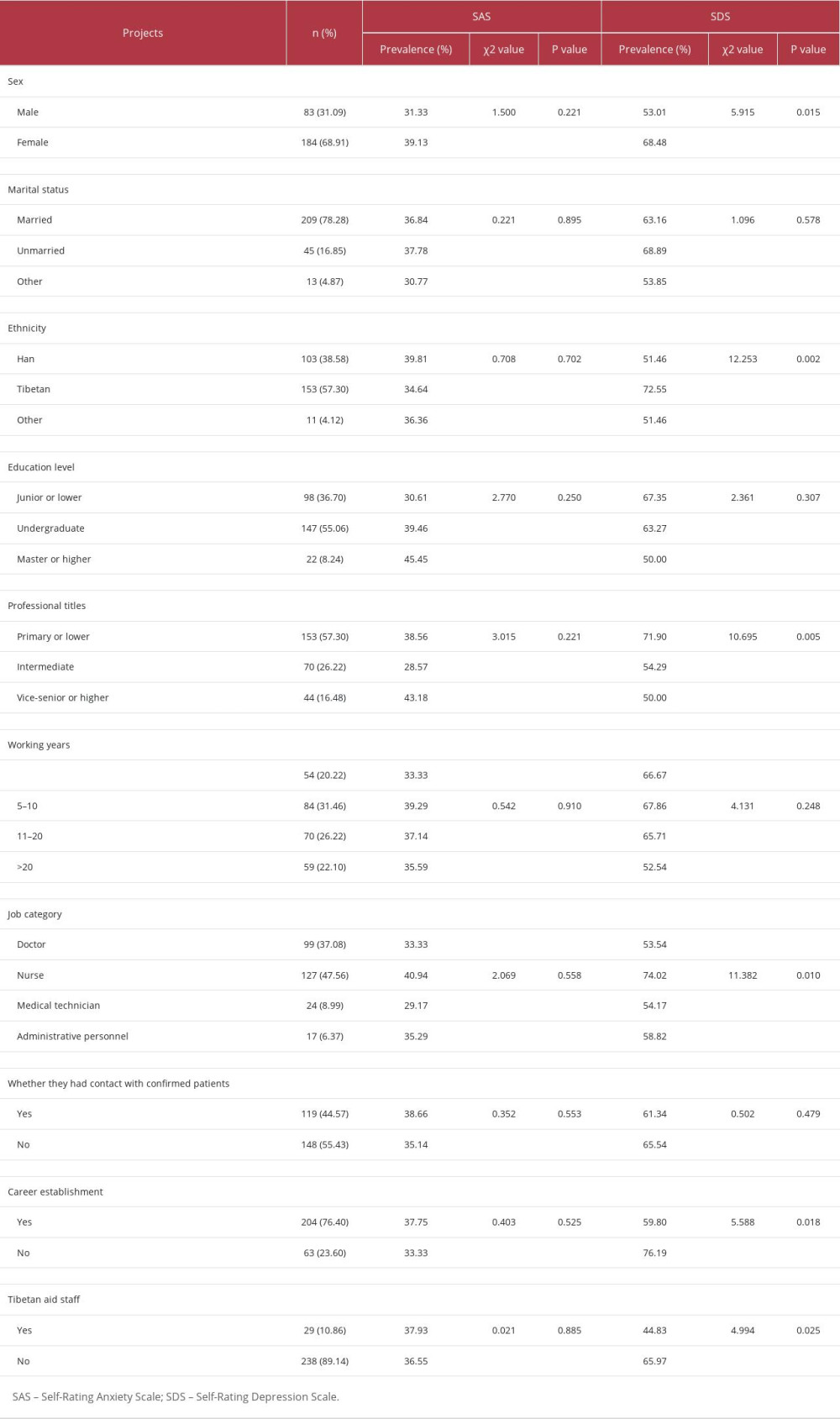

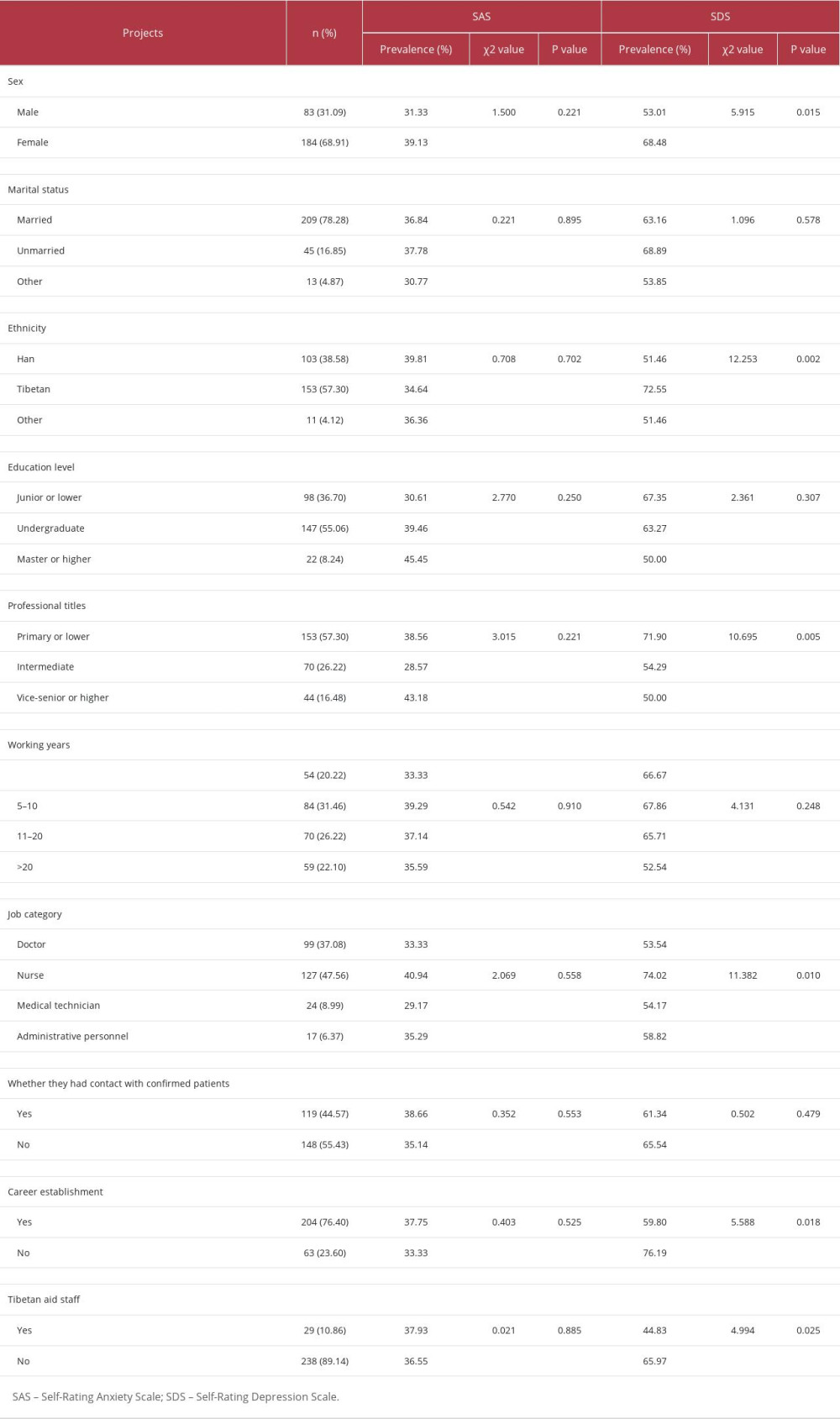

We investigated a total of 267 hospital staff in this study, of which 83 (31.09%) were men and 184 (68.91%) were women. Their ages ranged from 19 to 58 years, with an average age of 35.81±8.56 years. Moreover, 78.28% of the participants were married, 57.30% were Tibetan, 55.06% had a bachelor’s degree, and 57.30% had primary or lower titles. The demographic characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1.

EVALUATION OF ANXIETY AND DEPRESSION IN HOSPITAL STAFF:

The mean SAS score of the participants was 47.13±10.96, and anxiety was present in 98 participants (36.70%), including 63 participants (23.59%) with mild anxiety, 24 participants (8.99%) with moderate anxiety, and 11 participants (4.12%) with severe anxiety. The mean SDS score of the participants was 54.56±12.66, and depression was present in 170 participants (63.67%), including 74 participants (27.71%) with mild depression, 81 participants (30.34%) with moderate depression, and 15 participants (5.62%) with severe depression. A total of 84 participants (31.46%) had anxiety combined with depression. The prevalence of depression was higher in women, Tibetan personnel, hospital staff with primary or lower titles, staff without career establishment, and non-aid Tibetan personnel, and the differences were all statistically significant (P<0.05). For details, see Table 1.

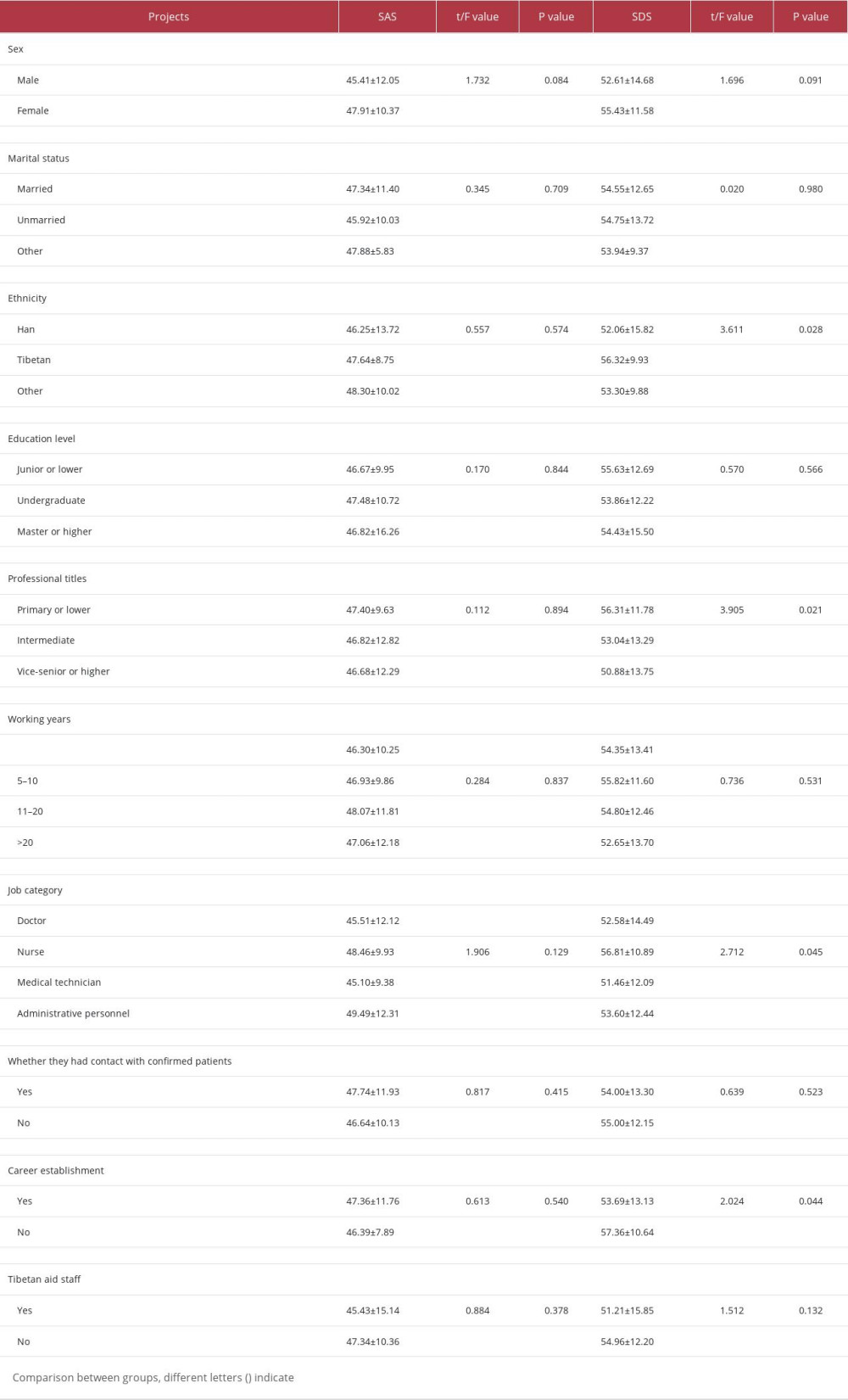

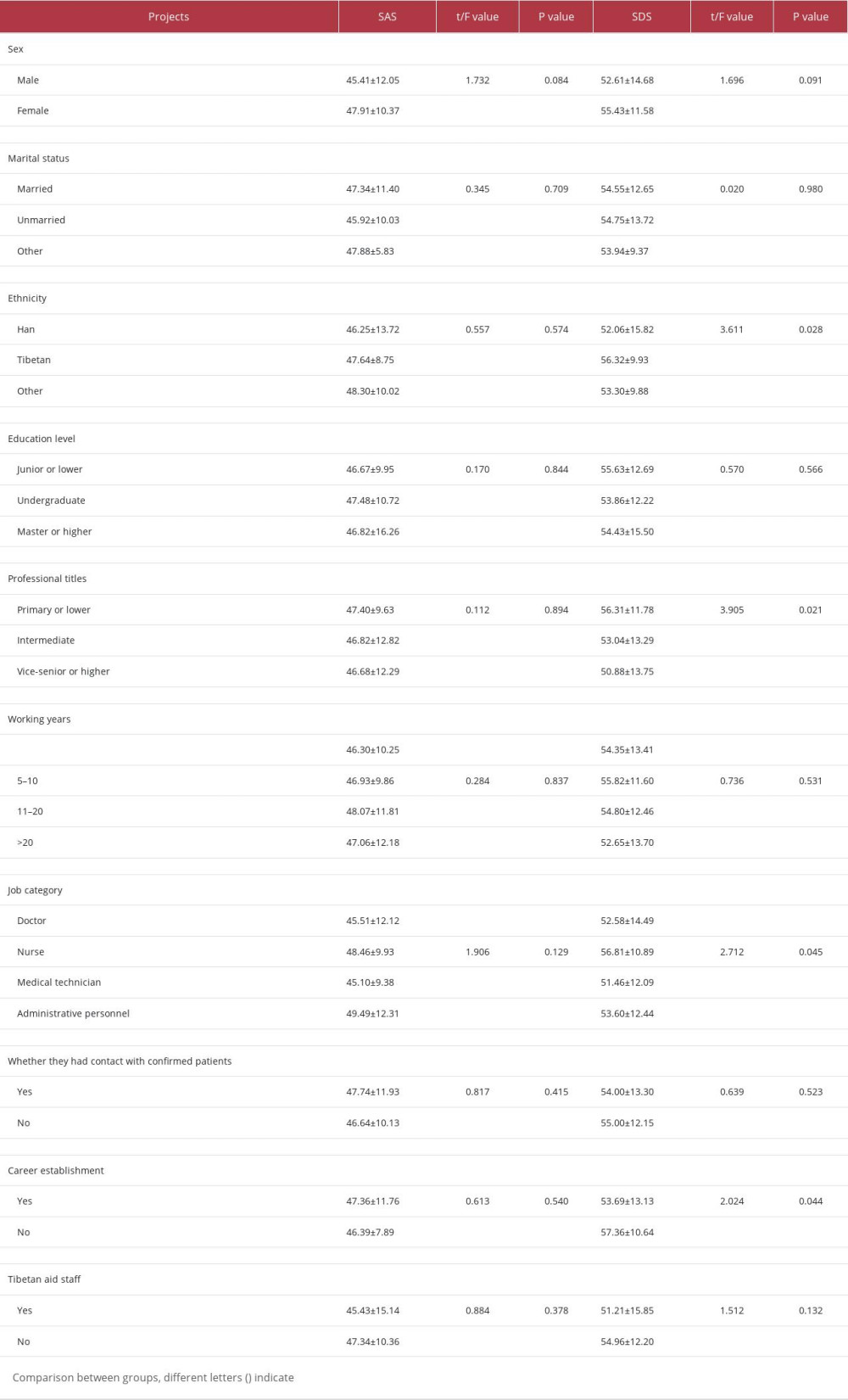

The mean SAS (47.13±10.96) and SDS (54.56±12.66) scores of all hospital staff were higher than those of the national norm SAS (37.23±12.59) [14] and SDS (41.88±10.57) scores [13], and the difference was statistically significant (P<0.001). Details are shown in Table 2.

COMPARISON OF ANXIETY AND DEPRESSION SCORES AMONG HOSPITAL STAFF WITH DIFFERENT CHARACTERISTICS:

The SDS scores of depression in Tibetan hospital staff, nurses, hospital staff with primary or lower titles, and staff without career establishment were higher, and the differences were all statistically significant (P<0.05). There were no significant differences in SAS scores based on the different characteristics of the hospital staff (P>0.05). For details, see Table 3.

Discussion

As an emerging infectious disease, COVID-19 spread rapidly and had a wide range of effects, and the population was generally susceptible to it. There was no approved drug treatment for COVID-19, adding to the serious impact on the social economy and daily life of the people. The hospital staff in Shannan People’s Hospital, which is a designated hospital, may have different degrees of psychological stress reaction in the face of public health emergencies. We used the SAS and SDS scales to investigate the mental health status of hospital staff on duty during the COVID-19 pandemic. The results showed that the anxiety and depression levels of hospital staff were significantly higher than those of the domestic norm (

The results showed that the prevalence of depression was higher in women, Tibetan staff, those with primary or lower titles, nurses, staff without career establishment, and non-aid Tibetan personnel. Our results suggest that great attention should be paid to the mental health status of these personnel. A meta-analysis showed that women, nurses, and staff with primary titles were more prone to depression [18]. Previous studies [5,19] had shown that women were more likely than men to experience negative mental health, and one study reported that changes in estrogen play an important role in female depression [20]. Women’s physical strength is generally lower than that of men, and a high-intensity workload may induce female depression. In addition, the majority of nurses were women, and treatment and nursing operations were performed by nurses, who spent more time in the ward than did doctors and had more frequent close contact with patients [21], which increased the risk of infection. Therefore, female medical professionals were more prone to depression, which was in line with results of previous work conducted during epidemic outbreaks [22]. Hospital staff with primary or lower titles had just started their careers, had limited knowledge and skills related to infectious diseases and treatment experience, and had not had many opportunities to receive training; therefore, they were prone to negative stress when facing unexpected situations.

The results supported the hypothesis that Tibetan hospital workers developed a higher level of depression when exposed directly or indirectly to patients with COVID-19. Once the first COVID-19 case was reported in Lhasa, the period of 920 consecutive days without an outbreak in Tibet was broken. Tibetan hospital staff had hardly encountered COVID-19 cases in the early stage and therefore lacked practical experience in infectious disease diagnosis and treatment, care, and use of protective equipment. This, coupled with the emergence of a large number of infected and suspected patients in a short period of time, caused difficulty in preventing and controlling the epidemic in medical institutions. The insufficient number of hospital personnel and the high intensity of work would all become sources of psychological risk [23]. A pre-pandemic study demonstrated that Tibetan students had higher depression scores than did Han college students in the Tibetan plateau region, again supporting our hypothesis [24]. Non-aid Tibetan hospital workers developed a higher level of depression. This may be because the hospital staff who assisted Tibet were mainly the seventh batch of medical team members from the Anhui Province, most of whom had experienced the COVID-19 pandemic firsthand and had certain working experience; therefore, the depression in this group was relatively low. Personnel who did not have career establishment had certain gaps in salary, insurance protection, promotion, and advancement, compared with those who had career establishment [25], and since bonus income was not guaranteed during the epidemic, these personnel were more prone to depression as they faced increased pressure from work and family. This was supported by previous research [26].

In addition, after the pandemic, the hospital had closed-loop management, hospital staff lived in the hospital or isolation hotel, normal life was restricted, and the staff could not see their friends and family for a long time; therefore, they were more likely to become depressed and irritable because they were worried about their lives and health [27]. The present study found no statistically significant differences in SAS scores and the prevalence of anxiety based on the different characteristics of hospital staff. This finding may be because the sample size was small, although we included the entire population of 300 hospital staff on duty. On the other hand, the prevalence of anxiety was relatively low, with small differences between subgroups. Therefore, the results should be considered preliminary and require further study.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study on the mental health of hospital staff in Shannan, China, during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nevertheless, there are several limitations of this study. First, we used least significant difference for post hoc analyses of multiple tests, which might have increased the probability of making type I errors because they could not be corrected. Second, all information was based on self-report measures that inevitably deliver a systematic bias in evaluating the target construct. Finally, our study was based on web-based questionnaires instead of clinical interviews, and therefore the point prevalence is often overestimated due to the low specificity of the tests [28]. Combining questionnaires and clinical interviews can reduce the rate of false-positive results.

Conclusions

This study suggests a significant psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on hospital staff in a designated hospital in Shannan. Specific attention should be dedicated to the identified vulnerable groups, such as women, Tibetans, those with primary or lower titles, nurses, those without career establishment, and non-Tibetan aid personnel. Medical institutions should cope with the psychological impact of the pandemic on hospital staff by routinely screening mental health outcomes, modifying working shifts, and reducing the exposure to frontline workplace hospital staff. The identified vulnerable groups should be provided with training, psychological support, and treatments when necessary. Early screening and intervention strategies in at-risk groups are extremely important to prevent the potential long-term adverse psychological effects of public health disasters such as the COVID-19 pandemic. On the other hand, further studies should attempt to investigate any possible protective factors or positive coping styles that may have protected hospital staff from the risk factors related to the pandemic.

Tables

Table 1. Comparison of the prevalence of anxiety and depression by characteristics of hospital staff. Table 2. Comparison of Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) and Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS) scores of 267 hospital staff with scores of the domestic norm.

Table 2. Comparison of Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) and Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS) scores of 267 hospital staff with scores of the domestic norm. Table 3. Comparison of Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) and Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS) scores by characteristics of hospital staff.

Table 3. Comparison of Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) and Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS) scores by characteristics of hospital staff.

References

1. Zhang WR, Wang K, Yin L, Mental health and psychosocial problems of medical health workers during the COVID-19 epidemic in China: Psychother Psychosom, 2020; 89(4); 242-50

2. Dragioti E, Tsartsalis D, Mentis M, Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of hospital staff: An umbrella review of 44 meta-analyses: Int J Nurs Stud, 2022; 131; 104272

3. Wang LX, Xu XM, Shi L, A cross-sectional study of the psychological status of 33,706 hospital workers at the late stage of the COVID-19 outbreak: J Affect Disord, 2022; 297; 156-68

4. Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019: JAMA Netw Open, 2020; 3(3); e203976

5. Lei H, Yang ZF, Mental health status survey on the first-line healthcare workers in designated hospitals for COVID-19 under the delta strain outbreak: Med J Wuhan Univ, 2022; 43(6); 897-901+907

6. Fu N, Liu J, Luo LW, Investigation on mental health of infectious department staff under the environment of epidemic prevention and control in novel coronavirus and analysis of countermeasures: Chin J Health Psychol, 2022; 30(7); 985-89

7. Chen Y, Wang J, Geng YJ, Meta-analysis of the prevalence of anxiety and depression among frontline healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: Front Public Health, 2022; 10; 984630

8. Neuropsychology and Behavioral Neurology Group, Neurology Branch, Chinese Medical Association, Expert consensus on the diagnosis and treatment of anxiety, depression and somatization symptoms in general hospitals: Chin J Neurol, 2016; 49(12); 908-17

9. Kircanski K, LeMoult J, Ordaz S, Gotlib IH, Investigating the nature of co-occurring depression and anxiety: Comparing diagnostic and dimensional research approaches: J Affect Disord, 2017; 216; 123-35

10. Zung WW, A rating instrument for anxiety disorders: Psychosomatics, 1971; 12(6); 371-79

11. Liu XC, Sun LM, Tang MQ, Analysis of the test results of self-rating anxiety scale for 2462 adolescents: Chin Ment Health J, 1997; 11(2); 75-77

12. Pang Z, Tu D, Cai Y, Psychometric properties of the SAS, BAI, and S-AI in Chinese university students: Front Psychol, 2019; 10; 93

13. Wang CF, Cai ZH, Xu Q, Evaluation of 1340 normal people by Self-rating Depression Scale-SDS: Chin J Nerv Ment Dis, 1986; 14(5); 267-68

14. Wu WY, Self-Assessment Scale for Anxiety (SAS): Shanghai Arch Psych, 1990(2); 44 New

15. Xu S, Wu JJ, Xu C, Survey of mental health status of first-line healthcare workers in designated hospitals for COVID-19 in Wuhan: Journal of Third Military Medical University, 2020; 42; 1830-35

16. Huang JZ, Han MF, Luo TD, Mental health survey of medical staff in a tertiary infectious disease hospital for COVID-19: Chin J Ind Hyg Occup Dis, 2020; 38(3); 192-95

17. Ga D, Basang KZ, Ynag LJ, Analysis of the current situation of anxiety and depression among clinical nurses in Tibet: Tibetan Med, 2022; 43(1); 3-5

18. Liu XY, Wang GP, Zhang J, Prevalence of depression and anxiety among health care workers in designated hospitals during the COVID-19 epidemic: A meta-analysis: Chin J Evid-Based Med, 2021; 21(9); 1035-42

19. Zhu JH, Sun L, Zhang L, Prevalence and influencing factors of anxiety and depression symptoms in the first-line medical staff fighting against COVID-19 in Gansu: Front Psychiatry, 2020; 11; 386

20. Albert PR, Why is depression more prevalent in women?: J Psychiatry Neurosci, 2015; 40(4); 219-21

21. Liu CY, Yang YZ, Zhang XM, The prevalence and influencing factors in anxiety in medical workers fighting COVID-19 in China: A cross-sectional survey: Epidemiol Infect, 2020; 148; e98

22. Rossi R, Socci V, Pacitti F, Mental health outcomes among healthcare workers and the general population during the COVID-19 in Italy: Front Psychol, 2020; 11; 608986

23. Cai ZX, Cui Q, Liu ZC, Nurses endured high risks of psychological problems under the epidemic of COVID-19 in a longitudinal study in Wuhan China: J Psychiatr Res, 2020; 131; 132-37

24. Gao L, Li FM, Gao XL, Relationship between sleep quality with depression and anxiety symptoms in college students at Tibet Plateau areas: Chin J Sch Health, 2021; 42(4); 593-596+601

25. Liu T, Yang XL, Wu D, Status quo of the occupational identity of in-service nurses in Tangshan and its relationship with psychological resilience: J Clinic Patholog Res, 2022; 42(11); 2769-75

26. Wesemann U, Hadjamu N, Wakili R, Gender differences in anger among hospital medical staff exposed to patients with COVID-19: Health Equity, 2021; 5(1); 181-84

27. Zhou XP, Huang JZ, Ren AK, Psychological coping ability of 1 426 health care workers participating in first-line anti-epidemic of COVID-19 in a city: Chin J Infect Control, 2021; 20(4); 320-26

28. Wesemann U, Applewhite B, Himmerich H, Investigating the impact of terrorist attacks on the mental health of emergency responders: Systematic review: BJPsych Open, 2022; 8(4); e107

Tables

Table 1. Comparison of the prevalence of anxiety and depression by characteristics of hospital staff.

Table 1. Comparison of the prevalence of anxiety and depression by characteristics of hospital staff. Table 2. Comparison of Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) and Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS) scores of 267 hospital staff with scores of the domestic norm.

Table 2. Comparison of Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) and Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS) scores of 267 hospital staff with scores of the domestic norm. Table 3. Comparison of Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) and Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS) scores by characteristics of hospital staff.

Table 3. Comparison of Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) and Self-Rating Depression Scale (SDS) scores by characteristics of hospital staff. Most Viewed Current Articles

15 Jun 2022 : Clinical Research

Evaluation of Apical Leakage After Root Canal Obturation with Glass Ionomer, Resin, and Zinc Oxide Eugenol ...DOI :10.12659/MSMBR.936675

Med Sci Monit Basic Res 2022; 28:e936675

07 Jul 2022 : Laboratory Research

Cytotoxicity, Apoptosis, Migration Inhibition, and Autophagy-Induced by Crude Ricin from Ricinus communis S...DOI :10.12659/MSMBR.936683

Med Sci Monit Basic Res 2022; 28:e936683

01 Jun 2022 : Laboratory Research

Comparison of Sealing Abilities Among Zinc Oxide Eugenol Root-Canal Filling Cement, Antibacterial Biocerami...DOI :10.12659/MSMBR.936319

Med Sci Monit Basic Res 2022; 28:e936319

08 Dec 2022 : Original article

Use of Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate and Urine Albumin-to-Creatinine Ratio Based on KDIGO 2012 Guide...DOI :10.12659/MSMBR.938176

Med Sci Monit Basic Res 2022; 28:e938176